Billee Pat Connolly

Content warning: Heads up, we want to warn our listeners that this interview includes descriptions of abuse and terms that reflect racist, sexist, and homophobic opinions and attitudes. These views and language do not reflect the Starting Line 1928’s views or opinions

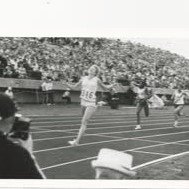

Billee Pat Connolly racing in her younger years.

When 16-year-old Billee Pat Connolly stepped up to the start line of the 800-meter race at the 1960 U.S. women’s Olympic Track and Field Trials, she had no idea she would become a part of history in what has now become known as "The Abilene 800," the event that opened the door for women to run longer distances. Connolly went on to become a three-time Olympian, a renowned track and field coach, who coached Evelyn Ashford and Allyson Felix to their own Olympic berths.

Born in an era (1943) when women were raised to be girlish with the single goal to find a husband, she also had a traumatic childhood, suffering emotional and physical abuse from both her parents. She started running from home by age 10 with multiple attempts. Her P.E. teachers described her as too aggressive when playing basketball with girls’ rules. Her mother entered her in beauty pageants and home economic classes, but Billee had other ideas. “I wanted to run away to the circus and be a trapeze artist.”

The circus would have to wait as Billee’s life took a turn toward sports when her driver-education instructor, who was also a coach of a nearby girl’s AAU track club, noticed her long legs and suggested that her dad take her to a track meet. That night, her step-dad, a former collegiate two-miler who saw her potential, asked Billee if she wanted to go to the Rome Olympics. “I didn’t even know what the Olympics were, but if it meant getting away from home I was all in,” recalls Billee.

At that AAU girls' meet, Billee won the broad jump and broke the meet record, making her think she was headed for Rome the following summer. Her coach, Ed Parker, however, checked the American records and decided her chances were better in the 800-meter run that was included in the Olympic schedule for the first time since 1928. "I loved jumping but if running the 800 would get me out of a hellish home life, I would do it."

She won the Abilene 800, breaking the Olympic and American records in a time of 2:15.6, barely ahead of Rose Lovelace by one-tenth. “Billee wanted it more than any of us," said Judy Shapiro who went on as a pioneer for long-distance running.

After the Trials, the USA Women's Track and Field Team was bussed to a month- long Olympic Training camp in Emporia, Kansas where Billee met the other half-milers, Doris Severtsen (Brown) and Louise Mead (Tricard). There she realized that the racist views taught by her parents in her sheltered Mormon upbringing were false. They had threatened Olympic Coach Ed Temple not to get close. "If he touches you I'll string him up."

Connolly at the 1964 Olympic Trials

As a result, Temple didn't coach her and the inexperienced teen was left on her own to carry the high expectations of feminists, racists, and Cold War patriots into the Rome 800. She was astonished when her Black teammates were encouraging, kind, and nothing like the description her parents preached. “They became my role models and friends.” states Billee. “They enlightened me, not just in sports but about their own Civil Rights struggles.”

That struggle was made real when she invited a Black teammate to go see the movie "The King and I" in downtown Emporia, because the response was, "I can't go to the movies. Girl, if I set one foot in there with you, I'll be strung up like Emmett Till." Later that night she remembered Francisi Kazsubski, AAU Women's T&F Chairman, saying we need more (white) girls like you in track. Someone else had said, "You are the Great White Hope."

Rome was not to be Billee's Big Escape. “I trained myself by watching my teammates and copied every movement and detail. That turned out to be a great education and helped me later when I became a coach.” She especially wanted to run like Wilma Rudolph. But being undertrained and competing against Russian, European, and Australian women who were running times under 2:10, she finished last. But finish she did, which was a major accomplishment as she had been warned to cross the finish line at all costs.

Billee went on to participate in the 1964 and 1968 Olympics in the pentathlon. She then embarked on a successful coaching career, becoming the first female track-and-field coach at UCLA and creating their powerhouse women’s team. Her advocacy for Black track-and-field athletes earned her a place in the African American Ethnic Hall of Fame. She also testified before a Senate committee on performance drug use in sports of which she is strongly opposed.

Billee Connolly’s life story is scattered with shards of childhood abuse, rebellion, forbidden love, awakening and finally defining herself on her own terms. Her advice to her competitive runners at every level--high school, collegiate, Olympic:

“You must do your best when it counts the most.” Billee made the best of her life against all obstacles.

Note about the author: Gail Waesche Kislevitz is an award-winning journalist and the author of six books on running and sports. She was a columnist for Runner’s World for fifteen years and her freelance work has appeared in Shape, Marathon and Beyond, and New York Runner.