Jacqueline Hansen

It was Jacqueline Hansen’s third marathon in three months and under normal circumstances, both her coach and her doctor would have strongly advised against her running the 1984 Boston Marathon. The former world record holder in the marathon had fought for the inclusion of the women’s marathon in the 1984 Olympics as president of the International Runners Committee and she was determined to make it to the trials starting line.

The weather could not have been more different than when she won in 1973. Instead of an unusually warm day, it was cold and hailing.

“I had seen the 25 mile mark that said I was on 2:44 pace and I was 10th place. And I wondered, how the heck did they do that? How did they do that. And that was like the last thing I really remember, and I'm kind of blacking out and I just got mad.” she said, “I have one mile ago and I've been working for so long. I've been working ten years. All I want to do is go to the Olympic trials. I just need to run a sub 2:50. I just need, I need this. You know, I deserve this, I deserve this. And that became my mantra. I deserved to finish.”

She woke up in the hospital with the doctor explaining that she had hypothermia. Her first question, “Did I finish? What was my time?”

Her time was 2:47:48, she had qualified.

For Hansen it started with the presidential fitness test. “I'm pretty bad at other sports and I was in high school and I dreaded physical education. I know it's really funny that I ended up being a health teacher and a physical education teacher, but I really didn't like PE.” she said, “Couldn’t do pull ups, chin ups,had no arms strength, no coordination, no flexibility, but I love the running part.”

In her senior year, the new PE teacher started a track team for girls. “I signed up, I also thought it might help me get a passing grade in my current PE class with her.” she said. The longest distance girls were allowed to compete was in the 400m and she was not fast enough to make it to the city meet. “I graduated high school and at least she (her coach) planted that seed and I kept running,” she said.

Hansen attended Pierce College, a junior college, while there the tennis coach volunteered to coach the women's track team. She taught each class like a skill class and Hansen tried each event. “We would stay after class and actually run. So we had a little contest. We'd like to see who could run the longest before quitting” she said.

While attending California State University – Northridge, she continued to pursue long distance running. There was no team and no coach. “So mostly I would either run by myself or maybe run with the men's team, but I didn't train with the men's team” she explained “And so I was running around campus one day and I bumped into another woman running and we became friends. I mean, it was so rare and her name is Judy Graham. And she said, well, I have a team and I have a coach. I run for the L.A. track club and you're welcome to join us. And I did. And that made all the difference.”

Jacqueline and her coach, Laszlo Tabori

At the L.A. track club she began training under Laszlo Tabori. “Well, all of a sudden, my life just revolved around my running and Laszlo gives double workouts. When I was training for Boston, I'm running in the morning before the sun came up and I'm running in the evening after the sun went down and in between I'm either going to work to support myself and my tuition or I'm in class trying to keep my grades up and stay eligible” she said.

It was while she was training for the 1500m (the longest distance women could run on the track), she witnessed Cheryl Bridges break 2:50 for the marathon at the Western Hemisphere marathon in Culver City. Having raced cross country and track with Bridges, Hansen thought she could do that too. With little marathon training, she won it the next year “So I went from crossing the line and saying never, ever again. I'm never doing that again to going to the awards ceremony thinking, you know, I can do better. I bet that next time if I trained for this, I could do better.”

When one of her teammates suggested that she run Boston, she was intrigued. To train, her mileage and number of intervals increased. She treated Boston like she was going hiking, wearing two pairs of socks and her heaviest shoes.

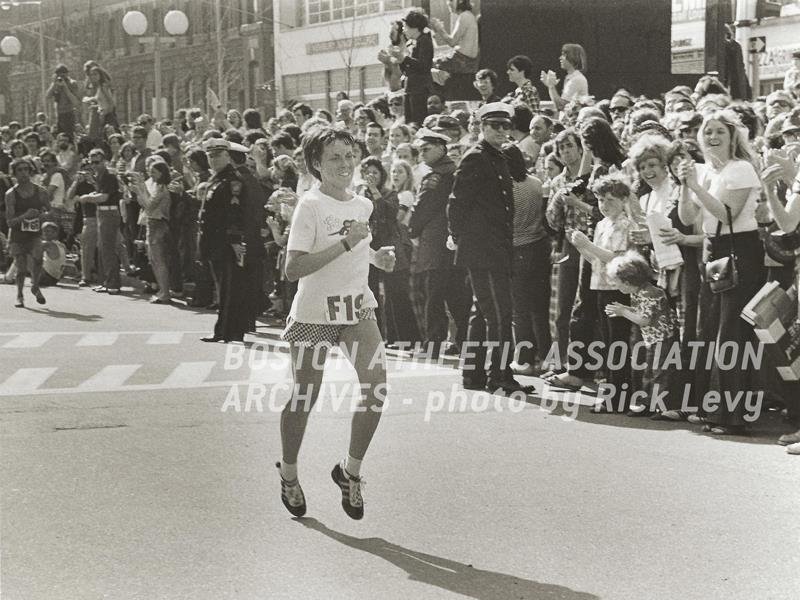

Boston 1973

“It was the biggest field I'd ever run in. It was probably a 1500 people total, but it was the biggest field I'd ever run in, especially because I came from the track, but it was bigger than Culver City marathon for sure. But I did feel I was running against myself and running against time. I had no idea I was leading until they started yelling it at me. I have a big old smile on my face, on the finish line,” she said, “Boston treats you so well, they've treated me like royalty ever since. It's always a treat to go back to Boston.”

After the win at Boston in 1973, she went back to racing track and cross country but added road racing to the schedule. She won the AIAW (Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women) title in the 1500m that same year. The NCAA did not stage a women’s championship in track until 1982.

“I do love a good mile; I still think it's my favorite. There's nothing like having a well-executed race plan and having it work when coming across the line first” she said.

She returned to the Western Hemisphere marathon in Culver City to set the world record for the marathon in 1974 with a time of 2:43:54. It felt like at the time, every time she raced the distance, it was a PR. In 1975, she passed up the National Championships because she did not think she was running enough mileage and instead opted for Nike OTC Marathon. She arrived with no illness, no setbacks and no injuries. Before the race, she met with a group of runners to tour Eugene. Eventually, the conversation came to goals for the upcoming marathon.

“And I just blurted out of nowhere. I want to run six minutes a mile. That's my goal. And then it got real quiet and people are doing the math in their head and it must have sounded a little precocious” she said. Looking back, she now realizes that she was declaring her goal.

OTC Marathon - World Record

“Everything went right. It was effortless. It was euphoric. I was clicking off the miles, 6:08 at the slowest 5:50s at the fastest and those were the last 10 kilometers,” she said, “I crossed that finish line, I thought I could turn around and do it again. It was like no time passing. It was completely effortless. And yet at the same time, I remember all these markers and times and my water. I had a clear sense of every single mile, but I didn't feel like I had run at all. I felt completely fresh at the finish. An amazing experience. It's the kind of thing you wish you could just pull it out of your repertoire anytime and do it.”

The Olympics were in Montreal the following year and she thought with a letter writing campaign that she could get the women’s marathon added to the games. She explains “Maybe nobody asked the IOC maybe we should do that. Maybe we should have a letter writing campaign. Maybe we could circulate a petition. Maybe we can get this done in time. But what really came to pass was in 1979, while my husband was working for Nike, Pam Magee was the women's rep at the time. And she got the brilliant idea to pool all our efforts.”

The International Runners Committee was formed with Hansen serving as president. They brought on a statistician, hired a lobbyist to teach them how to lobby and had a medical professional to defend that they were not the weaker sex. They proved every criterion to add a new sport even though it was adding an event into a sport. The committee received support from Nike, which ran full-page advertisements in several running magazines calling for a women's Olympic Marathon. They were able to have vote to include the women’s marathon in the 1984 Olympics and it passed but they still didn’t have the 5k or 10k. “Now you're asking women to choose between 3000 or 42 kilometers. And this is unfair” she said.

Jacqueline and Joan Benoit Samuelson stand in front of a marker commemorating the Joan’s win.

In 1983, they brought a suit in California state court against the IOC asking for a mandatory preliminary injunction which would require the Olympic organizers of the 1984 Summer Games to include both 5,000 meter and 10,000 meter running events for women. Hansen found out that they had lost the lawsuit after finding out that she had qualified for the marathon trials. In a day, she had said she experienced the highest of highs and the lowest of lows.

“But I say that you can lose a battle and win the war. And they did put our events in. In the next 30 days, they announced when the five and ten were going in, so we ultimately won if not in court, making headlines in the newspapers. I'm more proud of my role than any world record. I'm just really proud of the IRC and the work we did” she said.

She made it to the start line of the 1984 Olympic marathon trials three weeks later. “I tried my best until I couldn't anymore. And then I walked and jogged in, in about three hours. Everybody patted me on the back. Everybody encouraged me, everybody as they passed me offered a kind word. It was about camaraderie and the celebration” she said.

At the first women’s Olympic marathon in Los Angeles, she collected bags as a volunteer and got to witness it firsthand. “It was like a dream come true. That the marathon came to me and women were in it and my best friend (Joan Benoit- Samuelson) won it. It was all good” she said.

Hansen now teaches in the school of education at Loyola Marymount and coaches, including for World Record Camps.

“It's been a journey. If I had it to do over again, I would do it exactly the same way. Maybe I didn't stay competitive in the marathon long enough to take advantage of it or benefit from it. But I'm really, really happy to be part of the change. And that's the best part. We have come a long way” she said.

Note about the author: Cara Hawkins-Jedlicka is a longtime supporter of women’s running and is part of the leadership team for Starting Line 1928. She is currently an assistant scholarly professor at Washington State University in the Murrow College of Communication.

You can follow Jacqueline on Instagram, and Twitter. See all her training logs and more on her website.