Julia Chase-Brand

Over 70 years ago, Julia Chase-Brand asked her mother why she wasn’t given a middle name like her four brothers. Her mother replied, “Because you’re a girl. You have to earn your own third name.”

Now 81 years old, Julia has made quite a name for herself in both the running and academic world. But her success didn’t come without facing much gender bias.

Julia grew up in rural Groton, Connecticut with two older and two younger brothers. She recalled one of them taunting her, “We changed doctors after you were born because we didn’t want another girl.”

Julia Chase-Brand running in 1961

Some days she would canoe to school and other days she would run. When she was five years old, her grandfather brought her to the track to run a mile with her brothers. By the time she was seven, she knew she wanted to run the Boston Marathon, even though women were banned from running anything more than 200 meters in a sanctioned competition.

But her life changed in high school when she encountered Olympian and Boston Marathon legend Johnny Kelley during one of her runs along the local railroad tracks. She was soon training alongside Kelley and being coached by his training partner, George Terry.

Her first official race was a big one: the 880-meter race at the New England track championships in July 1960. Wearing her brother’s holey T-shirt and old sneakers, Chase-Brand set a New England record and won by about 30 seconds. The win qualified her for the Olympic Trials in Abilene, Texas where women were allowed to run the half-mile for the first time since 1928.

Julia races Chris Mckenzie

People were so excited for her win they went out and collected money for her to travel to Abilene. Her coach insisted her tennis sneakers weren’t appropriate for the Olympic Trials, so he insisted she put on his shoes that were three sizes too big and taped them to her feet. “I was staring at the starting line and felt like my bra was suffocating me, so I ducked under the stands, reached under, and took my bra off,” she recalls. She then shoved it in her coach’s pocket. She took eight seconds off her New England time in those shoes.

Her mother wasn’t fond of Julia running distance and used Olympic track star Babe Didrikson as an example to dissuade her daughter. “She was so flat chested. And, of course, when she got married, she couldn’t have children and then died of cancer young,” her mother warned her. “My mother had an inheritance. I knew I only had myself to depend on,” says Chase-Brand, “That’s where some of my drive came from.”

Her father, a Rhodes scholar, came to her gymnastics and swimming events, but not running. When she returned from the New England champs where she’d set a new record, she recalled her father’s response: “He went stone quiet and said, ‘Maybe you’d like to play tennis?’ Running was lower class, tennis was for upper class.”

Julia flipping

To complement her training, Chase-Brand was also a trampolinist. “I had to flip onto a six-foot man,” she recalled. While studying at Smith College, she participated on the swimming and bowling teams while continuing to run on her own.

By 1960, tensions and momentum were building in both support of and opposition to women’s distance running. Chase-Brand decided to push the envelope by entering the historic 4.75-mile Manchester Road Race. But in her attempt to sign up, she was physically pushed out of line. Officials told her she’d be banned from all races if she signed up. She knew of another female runner whose coach had been arrested for letting her run, so she decided not to sign up for fear of harming her male friends who’d brought her to the race.

“In a way, I was a logical woman to challenge the ban on women’s running,” said Chase-Brand who comes from a long line of suffragettes and pioneers. Her great-grandfather was president of the American Woman Suffrage Association in the late 1800s and her grandmother was a leading suffragist and politician.

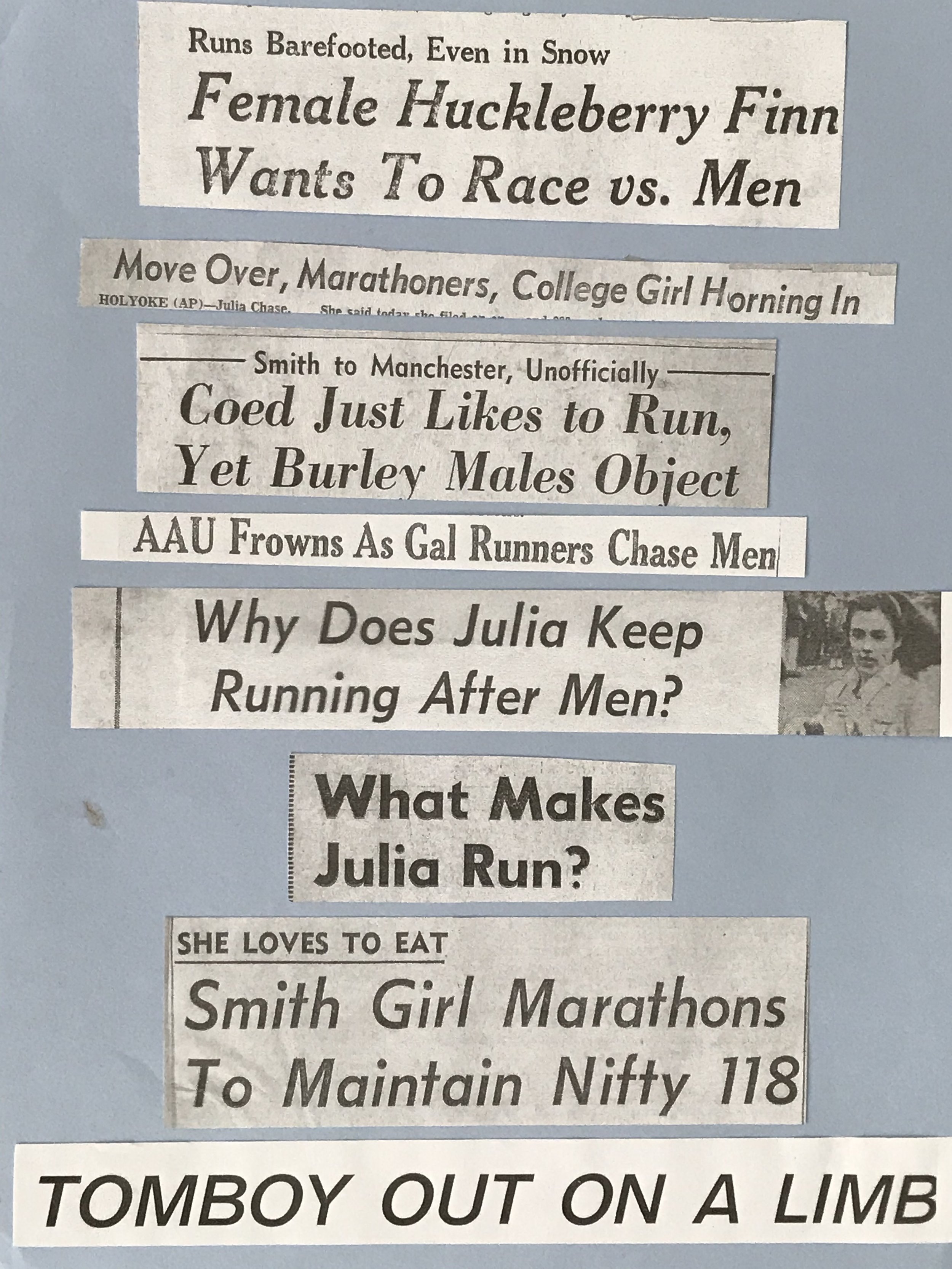

Once newspapers got wind of her wins at smaller races, the interviews took off. Headlines included, “Move Over Marathoners, College Girl Horning in,” “Coed Just Likes to Run, Yet Burly Males Object,” “Why Does Julia Keep Running After Men,” “Smith Girl Marathons to Maintain Nifty 118 Pounds,” and her favorite, from Life Magazine, “Tomboy Out on a Limb.” In reference to her physical measurements she was asked for, one writer wrote, “Eyewitnesses say they’re very good.”

The paparazzi became a little stressful, said Chase-Brand. “I began to feel like I was a one-dimensional cartoon character. My little brothers and George treated me as Julia. To the rest of the world, I was a freakshow.”

She received mail from strangers all over the world, from lovesick GIs in Japan wanting to be her pen pal to a Polish nudist wanting the traced outline of her foot. “They were all supportive,” she recalled.

She also received a letter from the A.A.U. (Amateur Athletic Union) informing her that if she entered the Manchester Road Race, she’d be banned from all athletics. Nonetheless, she showed up on Thanksgiving Day 1961, to run. “I was not trying to masquerade as a man,” she said. She wore a jumper with a skirt (her Smith College gym outfit), her hair long and curled, makeup and her crucifix necklace. This time she was successful in not only entering but crossing the finish line and beating several men.

Two months after the event, the A.A.U. sent a letter to her coach (not Chase-Brand), “If you, Julia, promise to never embarrass again this way by running on the roads, we will start allowing cross-country for women this spring.”

In many ways, Chase-Brand’s participation in the Manchester Road Race opened doors for women’s distance running. But she would continue to face opposition, even from other women in her sport.

At the 1962 indoor national track and field championships, the female president of the women’s A.A.U., put her arm around Julia and pointed out Grace Butcher who had won multiple 880-meter national championships. “Julia, you’re so pretty, you shouldn’t be running distance. You see Grace down there? She used to be so pretty before she tried running distance. Don’t do it, Julia.”

Male medical practitioners warned her she was going to compromise her fertility by running. Worried, Chase-Brand wrote to Butcher, a mother of two, who told her she’d be fine and to keep running. In her 30s, a young gynecologist told her, “It’s clear you are half-female and half-male because you’re so aggressive. You got a PhD, didn’t you? That means you’re aggressive. And the running just goes along with it.” He hadn’t even touched her yet.

After six years of competing, Chase-Brand gave up running when she went to graduate school where she dealt with more sexual harassment and discrimination. While working on her PhD she was incorrectly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and told she’d soon be in a wheelchair so she should break up with the guy she was dating and enlarge her doorways. She rearranged her plans and temporarily quit her PhD program.

Julia and Amby at the Manchester Road Race at the 60th Anniversary

Despite these obstacles, Chase-Brand once again found ways to excel. For many years, she worked in a variety of research and academic positions and raised her own family before returning to the classroom as a student. She completed her medical degree when she was a grandma of two and later became the medical director of outpatient psychiatry at Lawrence and Memorial Hospital.

In 2011, her running career came full circle when she returned to Manchester to race. She again wore her Smith College tunic, but this time her family accompanied her in full support.

Note about the author: Amanda McCracken is a freelance writer, runner, coach, and mother living in Boulder, CO. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, Guardian, NPR, Elle, ESPN, Outside, Women’s Running, Runner’s World, and Women’s Health. You can follow her on Instagram or learn more about her on her website.