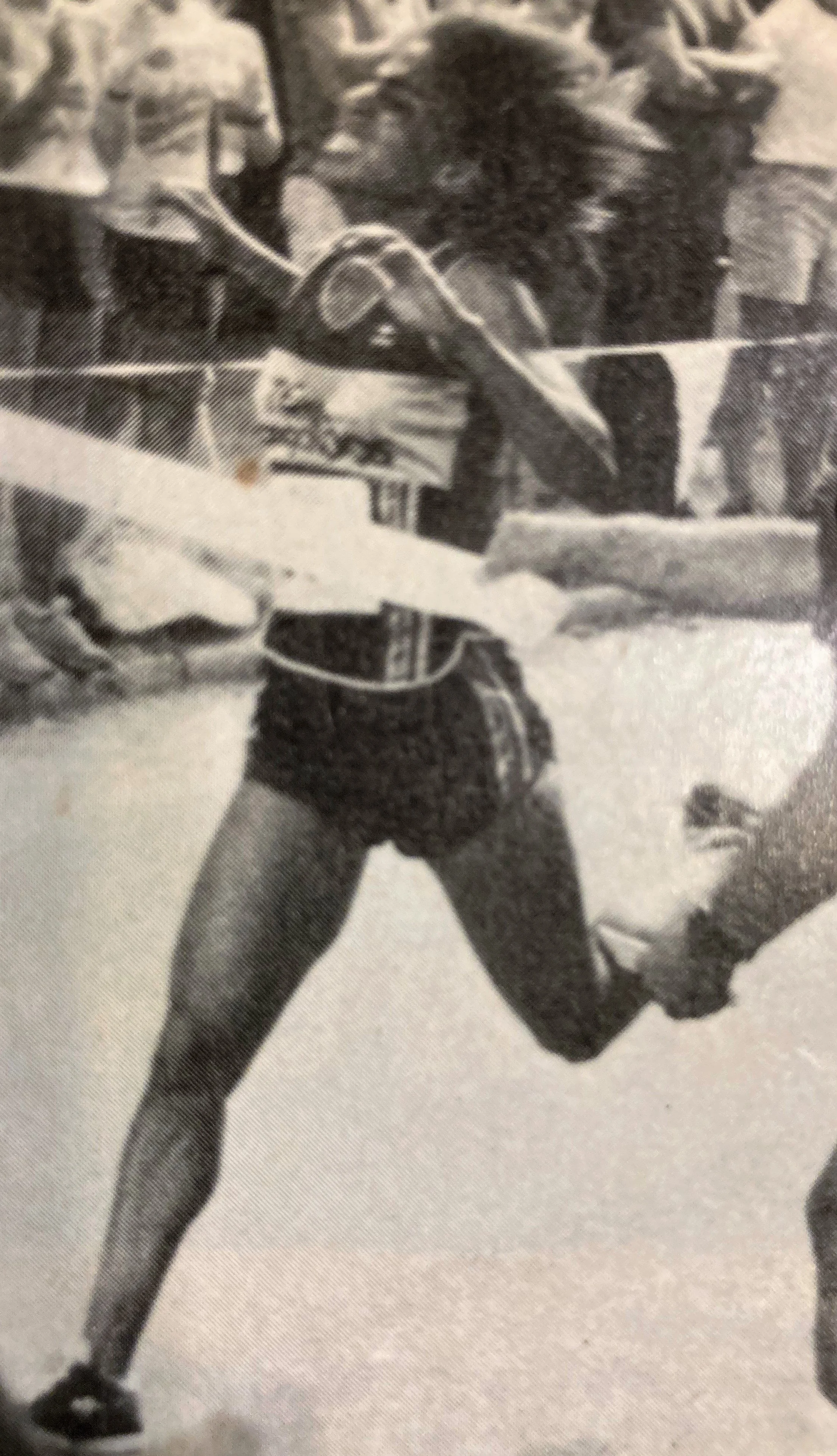

Michele Cuke

When high schooler Michele Cuke (née Bush) ran her first marathon, she couldn’t have imagined eventually becoming the fastest American-born Black female marathoner. And how could she have? She entered the race on a whim. “I heard about a marathon, and I heard about Miki Gorman, and she was going to be running the Santa Monica Marathon and I jumped in. I remember taking seventh [place],” Cuke recalled. “It was just something that I did for fun. I had no plans on running a marathon again.”

Seven years before her impromptu marathon debut, Cuke’s first racing success came at age ten when she won a 600-meter race sponsored by her church. She deemed that moment “an eye-opener for me, that running was something that I loved and I was good at.” Cuke went on to become one of California’s top high school 800-meter and cross-country runners, and received a number of scholarship offers to run collegiately. She had to be picky about the offers, though – and not for the same reasons as most highly-touted high school recruits.

Cuke was raised Seventh-day Adventist, which precludes her from doing secular activities on the Sabbath (from sunset on Friday until sunset on Saturday). In her junior year of high school, she recommitted herself as Adventist and stopped running on Saturdays. That meant no training, or racing, or even spectating on a day when races and track meets are frequently held. Of all the scholarship offers she received, only UCLA recognized that she would not run on Saturdays, so she became a Bruin. Cuke regularly topped the podium throughout her career, yet her running always remained in second-place behind her faith.

UCLA suited Cuke exceptionally well. She ran all four years, culminating in setting the 10,000-meter school record and becoming the 1983 NCAA 1500-meter champion. Cuke’s exceptional versatility allowed her to train for the 1500-meters – her preferred distance, although she frequently could not compete because the races were often held on a Saturday – while also excelling in the 10,000 meters, which was generally not contested on Saturdays. In Cuke’s sophomore year, the NCAA 10,000-meter race was unexpectedly moved to a Saturday to avoid impending hot weather. She was devastated to miss it, particularly after not running the race her freshman year due to a registration error. “Not being able to run my freshman and sophomore years, the passion and the drive were so much greater, and I didn’t give up.”

The summer after missing the 10K for the second time, Cuke unleashed that pent-up passion and drive to run 2:39:07 at the 1981 Avon Marathon, earning the designation of fastest American-born Black female marathoner – a title she maintained until 1989. “What was interesting, though,” she reflected, “is I don’t think I saw myself as a marathoner. I don’t remember planning another marathon after that.”

She returned to the track her junior and senior years, where everything finally came together for her to win the NCAA 1500-meter title, which she considers her greatest running accomplishment. After all of the missed races and time spent wondering what she might accomplish if given the chance to prove herself, this victory in her favorite event “represented a lot of growth to be able to persevere under dire circumstances.”

After graduating from UCLA with a degree in psychology, Cuke continued her literal and figurative pace post-collegiately while studying nursing at Columbia University. Under the tutelage of coach Tracy Sundlun, she maintained high-level training and globetrotted to races in a variety of distances. “I was racing a lot because there was a lot of prize money. I was able to win, or come in the top three,” she noted. Eventually Sundlun started negotiating appearance fees, so she was getting guaranteed money in addition to her winnings. “Even though I was a nurse, I’d say for years I did road running full-time, or I would do nursing part-time. There was money in road running, and I could support myself.”

Cuke regained her status as the fastest American-born Black female marathoner with a 2:37:41 at the 1991 California International Marathon. “Everything came together. I remember coming around the corner, approaching the finish line, and the guy was like ‘You got 2:37 today, Michele’ – and I feel the chills now.” To this day, she remains second-fastest on the growing list of American-born Black female runners who have eclipsed three hours in the marathon. Remarkably, she has been either first or second on that list since 1981.

Ultimately, Cuke completed eleven marathons in less than three hours, including eight in less than 2 hours and 45 minutes. The only marathon that took her over three hours was the spontaneous one in high school, which she completed in 3 hours and 23 minutes. Despite her long-distance success, Cuke considers herself a middle-distance runner at heart. Given her versatility, it seems appropriate to call her an all-distance runner.

Cuke, whose deep humility masks a fierce competitive drive, continues to run for fitness, but hasn’t raced in years. “If you put me in a road race right now, I would be competitive. And that’s why I don’t compete. I would go right back to training. I have no joy in jumping in a race and finishing in 50th place. I’m going to say, ‘I’ll train and come in 40th, then I’ll train and come in 30th…’.”

Cuke and her husband, Pastor David Cuke, have three grown children. The couple recently moved to Alabama, where Cuke works as a medical exercise specialist. Earlier this year she was inducted into the National Black Distance Running Hall of Fame, an honor she described as one of the biggest surprises and joys of her athletic career. “What I did could have easily been forgotten,” she said earnestly. “It was really, really special to me that they remembered it.”

Sarah Franklin is a writer, runner, and mother living outside of Boston. Her running-related musings take shape @the_runtrovert on Instagram.