Patricia Barrett

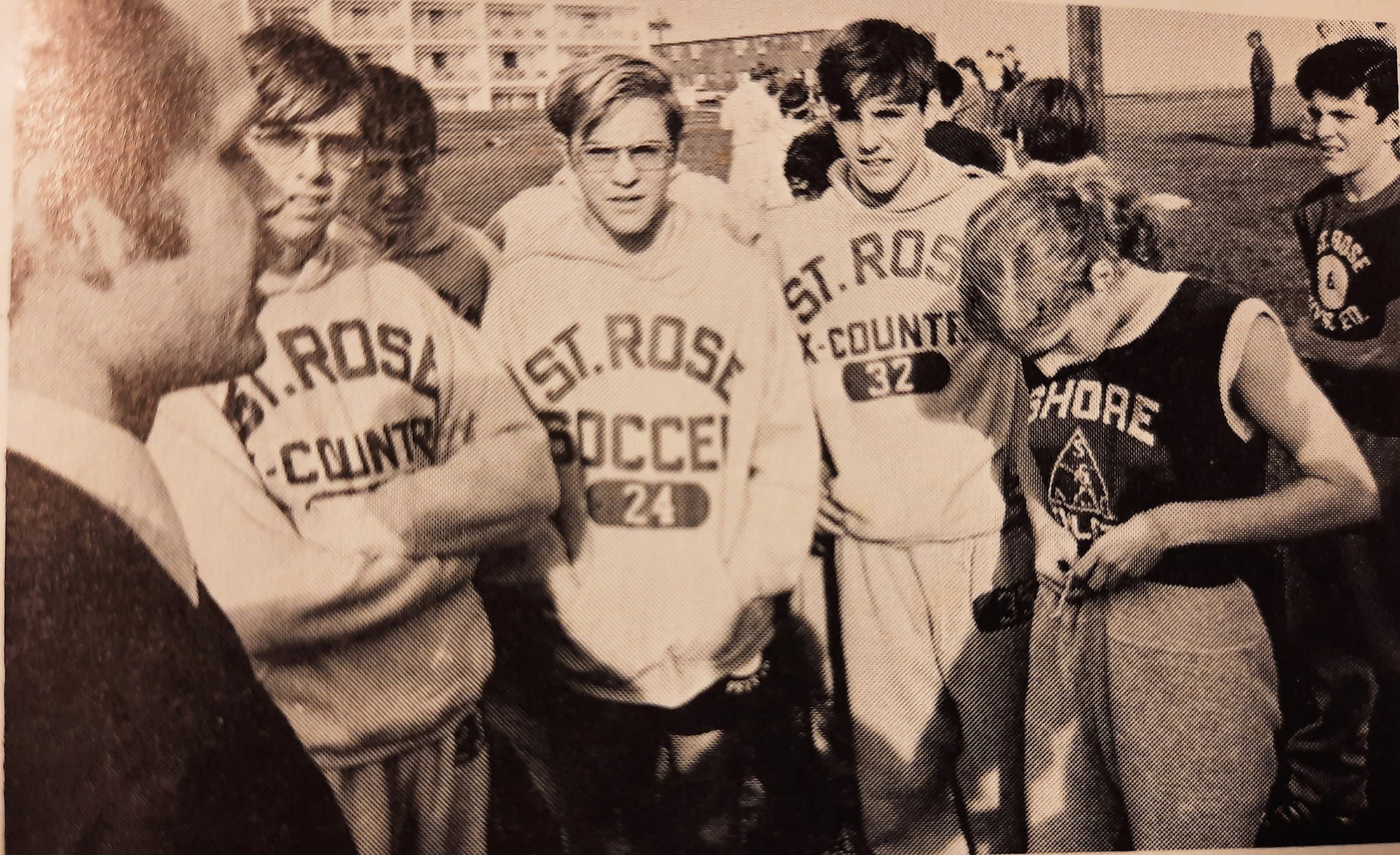

Training & racing with St. Rose HS Belmar, NJ (Silver Lake)

1972 was a banner year for American women in athletics, and Patricia Barrett, a high schooler from New Jersey, was at the center of many of the milestones.

In January that year, she won her first marathon, the inaugural Jersey Shore Marathon, which she entered because the boys on the cross-country team at St. Rose High School “challenged” her to do it. Her longest training run was 13 miles.

It was a cold, windy day along the coast, she remembers. “I finished it in like four hours or something, but I figured, well, this is interesting. But it was rough.”

Then she traveled to New York City’s Central Park for the Cherry Tree Marathon March 19, which she finished in about 3:24, fast enough to qualify for the Boston Marathon.

In New York she met Nina Kuscsick, who would become her role model (and who became the first woman to break three hours in the marathon twice that day). Barrett told Kuscsick she wasn’t sure if she should run Boston because it was close to her high school state championship track meet, where she planned to run the mile. Barrett had won a high school state cross-country title the previous fall.

“We need the women there,” Kuscsik told her. “If you don’t run, I’m gonna break your legs.”

“She didn’t really mean it,” Barrett recalls.

After consulting with her coach Bill Motzenbecker, Barrett was one of the eight women who ran the Boston Marathon that year, the first year female runners could officially enter and receive numbers, finishing in 3:40:29. It was a hot and humid day, which affected her time, Barrett said,

Before the 1972 Boston Marathon

“So when I get up there, my time wasn't very good. But I managed to get through it. And that was the important thing then to get through this race, because there was a lot of pressure to have women …finish this,” she said. “All these eyes were looking on us, we had to prove ourselves. And that's where a lot of the pressure came in. And I'm very proud. At that time, there were eight women, all of us finished. And…it was wonderful.”

But despite having to prove themselves to the sport’s officials from the Amateur Athletic Union, the male runners didn’t take issue with women running.

“Most of the men were very helpful. Actually, it was usually the AAU at the time, the governing body, who was giving us a hard time,” she said.

Barrett also said she always had support from her parents and from the nuns at her school.

“I was very lucky that my school was very supportive of me, and the Sisters of St. Joseph [are] wonderful. They wanted the women to go out and have the opportunities,” she said. The sisters didn’t mind that Barrett ran with the boys’ team, and they said she could miss school for the Boston Marathon.

1972 Crazylegs Mini Marathon

She returned to New Jersey and won the mile at the high school state meet in 5:35 just three weeks later.

Barrett was also one of 72 women to compete in the six-mile “Crazylegs Mini Marathon” in Central Park, the first women-only road race, in June 1972.

Three weeks after the race, on June 23, President Richard Nixon signed Title IX into law, barring discrimination based on sex in institutions that receive federal funding.

By this time, Barrett, though still a teenager, regularly joined the Shore Athletic Club for Saturday long runs ranging from 15 to 19 miles. There she met other runners to train with including the doctor and writer George Sheehan, known for his many books about the sport.

That fall, she returned to Central Park for the New York City Marathon, joining Kuscsik and five other women in a 10-minute protest at the start of the race.

Because she was younger than the more high-profile advocates for women’s running like Kucschik and Kathrine Switzer, Barrett was less involved in formal efforts to change the sport.

New York City Marathon starting line protest

But when she got to the starting line, Barrett saw the women in the race had signs protesting the AAU officials, who wanted the women to have a separate start, 10 minutes before the men.

“I didn’t know what I was getting into,” Barrett remembered, but she knew she wanted to support the women.

“We sat on the ground when the gun went off” to protest the earlier start time. Barrett opted not to hold a sign because she was worried the AAU might take away her previous titles or otherwise penalize her. They got up and started running when the men started.

Officially, the women’s times had 10 minutes added as a penalty. Without the additional minutes, Barrett’s time was 3:19.

“I didn’t know what to do,” Barrett told a New York Times reporter that day. “I was just there to run. And anyway, I thought the AAU might do something to me if they saw a picture of me carrying a sign.”

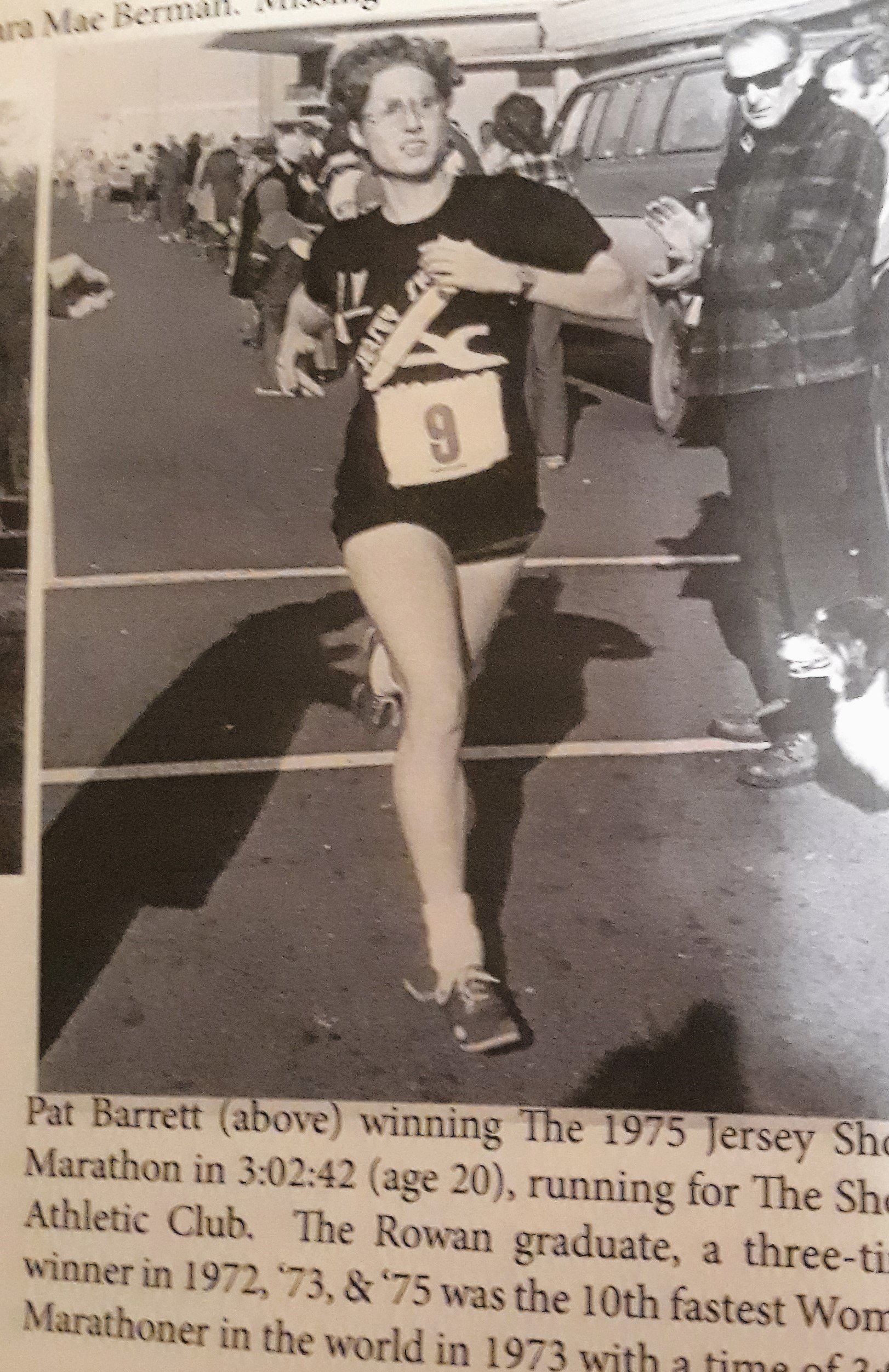

1975 Jersey Shore Marathon

She returned to the Jersey Shore Marathon in 1973, running 3:04, then the 10th fastest women’s time in the world. Dr. Sheehan would later mention Barrett’s performance in his 1978 book Running and Being—she beat him that day. She eventually ran her best marathon time, 3:02, at the Jersey Shore Marathon in 1975.

Although she witnessed so much history, Barrett recalls that, at the time, she didn’t see what was such a “big deal” about women racing.

Boston Marathon Celebration

“It wasn't really politics, for me, it was more like, I want to run, I have some talent, I want to be here. And I just want to participate like everybody today [is able to participate in running],” she said. “I guess I was an activist in a way. But I just just loved to do it.”

Note about the author: Laura Fay is a journalist and runner.